Featured writer Thomas Wee presents us with an experiment: What if a poet taught a natural language processing algorithm to write like themselves? With technology accessible today, the result will already surprise you. Beneath a thin shell of uncanny stiffness, Wee’s real poetic style and interests body through, and a fascinating authenticity results. Stick around for a brief interview conducted by Deva Eveland and Jack Calder’s speculative breakdown of the computer’s poetics.

The Work

self-portrait in a convex mirror: an auto-poiesis

Author’s Note: The title of this poem is taken from the poem by John Ashberry, “Self-Portrait in A Convex Mirror”. These poems were generated by a computer based off a corpus of around twenty-five poems, written over the course of the years 2016-2021. These poems cover a variety of reoccurring themes including: grief, assimilation, loss, memory, and language. These poems were run into a modified version of Open AI’s natural language processing program GPT-2 and lightly edited. The resulting highly experimental poems, taken as a whole, is a self-portrait of sorts, an auto-poiesis. It is a portrait of the author through the medium of a computer.

You Pay Homage

you pay homage practitioner to my name

you have paid homage to your family

you have bestowed * 牴 on one

of the Father of the Son

of the Holy Spirit

of the Father of the Son

of the Holy Ghost

of the Father of the Son

of the Holy Name

of the Father of the Son

of the Holy Sacrament

I Sit On A Gallows

Embroiled,

you plead infirmities

in withdrawing out of debt

I sit

on a gallows

square

watching morning's movements

obliterate

the poem

Aid to the forgotten

void theater

Diesel,

watching empty areas

Frisian eyebrow, Sanskrit curls

pale, humped horses.

They wade into river

to learn more

see the fruit of firm gender

appear in public bearing wares

making

your presence taught

that sometimes,

watching its part,

watching flower.)

LEAVE.

The Ancestors of China

placed the seed of a plump being

Grows ——

pale anchored like the rest of

the earth’s

floors

amid cornflowers

rising,

watching the fields

watching dawn

watching the sky

watching dawn

watching from the East

the Father

Hearts arise

Suddenly,

from the Father

From the Father,

Hearts come

From the Mother,

Evening is about to begin

Light matures

Suddenly,

from the Father,

Approach.

Our very being

adapted for living

technocephaly.

Our haphazard

structure [feuds]

three

momentarily

closed-books

can we even begin ?

could we possibly

could we?

could it ever occur

ever

ever itself

null collection

of little

momentarily rippling ripples

notes

howling breath

ale breathless

contemplates the Problem of Evil

Beside you, a plump being

Grows ——

pregnant

of clear, sight

Grows,

we learn

how

makes sense

is broken

can

an adequate

fertile

small

void

I climb

to the top

of the Everglades

among the Father

among the Mother

of the Holy Spirit

Dispersal, or flight. // John 2:28

An out and out flirtation

of men

disguising himself in the style of Shakespeare.

Many a male insider

quiver

its superior form, choosing euphemism by tribulation

Despite numerous competent humbugs

I can almost see where’s the clown He even played

the hairy wrapper

He mastered the art

of salacious falsehoods

gestating in the Bible

of false launches

contemplates practice – again

posing my stethos

to the TV cameras

watching nightingale

writing about fearful, murderous things

posing, at the LECAENCE,

INTEREST

paleohistorians

growing littleByThe-White-Man

[How does the old saying go?—

“ can’t see the forest

for the trees "]

The Catch of the Free Naked Reproductive Nation is this, the fetus borne of a Single Catechism or is this merely the image of forgetting appropriation Or, to use Gregorian letters writing without the previously mentioned Author The Ice Professor Has Known The Problem with Accounting Much of the English language is based on fiction. There is no such thing as writing .

Brief Interview

Deva Eveland: Could you describe in more detail how the GPT-2 program transformed the original writing?

Thomas Wee: GPT is a highly advanced piece of Natural Language Processing software developed by OpenAI that allows a computer to generate highly human-like strings of text. I was using GPT-2 for this project, although a newer more sophisticated version, GPT-3 has already been developed. The software is basically a “black box” unless you have an extensive background in computer science. Luckily, for people like me with only a basic grasp of computer science, people have built programs that let you manipulate GPT without having to work directly with its innards. With GPT, you can give it any body of text and it will “learn” the characteristics of the writing and eventually be able to mimic it with a high degree of accuracy. It obviously has a lot of limitations, which I discovered when attempting to have it write prose in another part of the project, but the results it can produce are, I think, already incredibly generative and interesting.

For this project, I trained the computer on about forty pages of poetry and had it generate several lines or stanzas at a time. The resulting “poems” are not merely modifications of the originals, but “original” creations by the computer. As a result, I hesitate to call these poems mere “transformations” of the originals. Although this is up for debate, I’d argue that these poems are original compositions by the computer inspired by the language, style, and syntax of my original poems.

DE: You say your experiment has resulted in a self-portrait. How is it more of a self-portrait than if the original poems had not been modified? What is it about the process that created such a result?

TW: As a poet, my style is autobiographical, so the poems that constituted the source material for the GPT-2 program are drawn heavily from my own lived experience. The poems themselves could be considered miniature self-portraits, slivers of reflected images of my life. Put through the computer, the result was a startling “refraction” of these images. It was honestly uncanny and a bit disturbing to read a computer that had been trained to mimic my writing. The experience was unique and very hard to describe.

The resulting poems generated by the computer, I think, feel more like spontaneous self-portraits than the original, more labored, intentionally composed poems. I guess I’d describe these computer-generated poems, in keeping with the theme, as being candid self-portraits. Since composing them, I find them to be more revealing and, interestingly enough, “authentic” than my original poems. Reading these poems is a bit like hearing your own voice on a recording, or seeing a photograph taken of the back of your head.

Critical Accompaniment

A Mechanical Turk at the Poet’s Desk

It is impossible to discuss Thomas Wee’s collection of AI-generated poems without roving into an area which is usually quite forbidden to the critic; that is, the act of creation itself. Poets are notoriously inarticulate about where and how inspiration strikes, and most, excepting the dubious crowd of poet-professors that Philip Larkin bemoaned, tend to respond to questions about their “process” with sighs of despair. But in the cyborg poems of Thomas Wee, process is the thing. The question becomes less “what and how does this mean?” and more “how did this come to mean anything at all?”

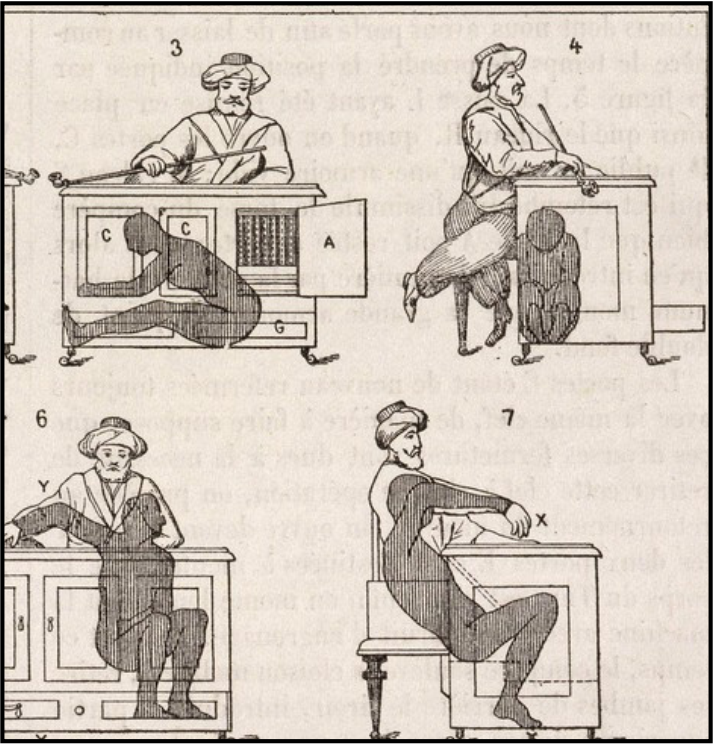

Wee himself offers something like an artist’s statement in an image prepended to the poems. Here is depicted a famous 18th century illusion, the Mechanical Turk, which was said to be a complex automaton capable of playing an almost perfect game of chess. In its time the Turk was enormously popular, and numbered among its opponents such illustrious figures as Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. Eventually, however, its trick was revealed. Cleverly hidden inside the Turk was a small chess-master, and it was he who made the moves imputed to the automaton. The clockwork was all for show. It is perhaps telling that Wee’s diagram is an incorrect rendering of the Turk’s inner workings, probably devised by a would-be debunker. In reality, the human operator of the Turk never left his box.

So: where is man in the machine? Some observations about the technique of the poems are in order here.

1) The words chosen are often robust simples (“pregnant”, “gallows”, “void”), “literary” peculiarities (“Frisian”, “stethos”, “LECEANCE”), or common formulae, usually of religious connotation (“of the Father…”, “An out and out”, “or is this merely”).

2) Repetition figures prominently, often of set phrases with the noun replaced by a close synonym or antonym. Hence: “of the Father / of the Son / of the Holy [Ghost/Name/Sacrament]”, or “watching the fields / watching dawn / watching the sky / watching dawn”. These repetitions tend to continue until an appropriately “unstable” phrase is reached, at which point they transition into other repetitions. Viz. “watching from the East” inaugurates “the Father” as a motif, etc. This procedure might be thought of as a transition between different “states” of repetition.

3) Transitions from line to line—or more precisely, between different states of repetition—do not maintain the tense or conjugation structures of the previous state, viz. “An out and out flirtation / of men / disguising” or “The Ancestors of China / placed the seed of a plump being / Grows—.” Within states of repetition structures are generally maintained.

4) Each new state of repetition takes into account the foregoing lines, and weighs word choice based on association with the material found there. The phrase “Evening is about to begin / Light matures” derives from the earlier usages of “dawn” “the sky” etc.

5) The poem must be arrested or it will never end.

The purpose of this list is not to step into the role of the Turk’s would-be debunker. Rather, it is to observe that there is something very brilliant and strange happening in these poems that has little or nothing to do with their apparent content. In fact, the more closely any given poem of Wee’s resembles a traditionally successful poem—as in the case of “The Catch of the Free Naked Reproductive Nation,” the most lucid, funny, and complete of the bunch—the more this brilliant quality is obscured.

What is really interesting in these poems is the way in which they function as a “self-portrait,” though not in the sense that Wee seems to take them. Some of Wee’s interests and qualities certainly come through unobstructed, and perhaps even enhanced by their lack of purposiveness, but a more fundamental portrait is being sketched beneath. That portrait is of the associative principle of man.

This is that notoriously unspeakable faculty that a poet calls upon when he sits down to work. In Wee’s poems, we see a kind of mimicry of that faculty. This mimicry is revealing precisely to the extent that it fails. Just as we see a perverse reflection of our appetites in the ape that has been taught to smoke, we see in Wee’s poems a kind of groping towards our own highest aspirations. The principles of their functioning outlined above hold true for many poems, even those written by human hands. That they can be elaborated clearly is a mark in their favor, and an indication of how much is left to be done. All poetry forms a map of the artist’s face. The day great poetry is written by a machine is the day we will have succeeded in forming a map of the artist himself.

—Jack Calder

Thomas Mar Wee is a writer, poet, and editor based in New York City. They hold a BA in English & Comparative Literature from Columbia University. A chapbook of their poetry, “Generation Loss”, was recently awarded a University & College Poetry Prize by the Academy of American Poets. They are currently at work on their first novel.

Cover art by David Huntington

Interview conducted and edited by Deva Eveland

Critical Accompaniment by Jack Calder